The unique experience of The Mountain is a growing sense of uncertainty whether you are outside looking in or inside looking out at the barbaric cruelty of the lobotomy. And though the film is delivered to you as a sort of arthouse drama, it is this underlying uneasy sense that actually makes The Mountain horror.

Mental illness has been the subject of film since the silent age. A madman’s dream (or is it a recollection?) is the storytelling device of the 1920 silent horror classic The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but the idea of madness in one form or another has been used and misused by filmmakers every which way in the 90 years since.

While horror films often play with the fear of being trapped in an institution, or a psychiatric hospital ward, they typically neglect the humanity of the conscious being trapped inside their own thoughts, their own body and a clinical system that might not understand them.

Nevertheless, director Rick Alverson (Entertainment, New Jerusalem) is far less interested in making horror than he is toying with the medium and the audience’s experience. Being disturbed or creeped out by the film is really up to you.

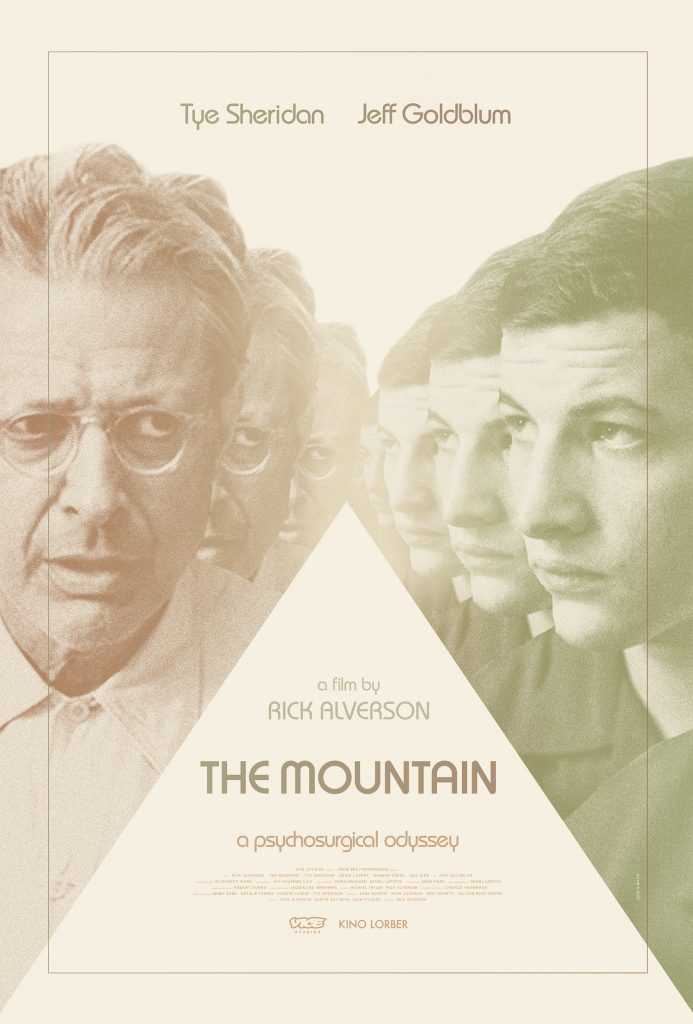

But his latest film follows a young misplaced man named Andy (Tye Sheridan) as he journeys with traveling lobotomist, Dr. Wallace Fiennes, played by Jeff Goldblum, from mental hospital to mental hospital. Andy’s voyage of self discovery is neither heartwarming nor freeing. Well, maybe. And the most delicate art of the tale is allowing you to decide if we are watching Andy or stuck in his skin with him. If we can feel a sense of doom that he can’t, or if, like him, we seem unable to change the path we’re on.

Alverson recently talked with Halloween Every Night about making The Mountain and drawing your own conclusions.

Halloween Every Night: After watching The Mountain, I couldn’t decide if the audience is outside looking in or inside looking out. Was that intentional?

Rick Alverson: If not entirely intentional, a very happy accident. I prefer there’s that vantage confusion. I think that’s really interesting. More than anything, i want us to be mildly conscious of the fact that we’re watching a film. I’m really interested in the threshold of the two-dimensionality of the screen and of being pulled into the narrative and the content and then being sort of alarmed by our relationship to these tropes of the protagonist and tropes of historic recreation and unlimited access to these places, events and people that is entirely privileged. I think too privileged. I think we need to become aware again of our place as audiences.

The protagonist Andy is intentionally a malformation of the sympathetic protagonist, which we have unlimited access to. He’s opaque. He’s a formal device. He’s a model for all intents and purposes throughout much of the film and we’re deflected around him. Yeah, that interests me.

HEN: Treatment of the mentally ill still seems to be lacking, but in the 1950s, with the use of lobotomies, it seems particularly brutal. How did the story come about?

RA: It’s kind of a continuation of a series of explorations of a particular utopian bent in the American male psyche. There’s this idea of lunging headlong … the event of progress that doesn’t take into consideration the ramifications of the act of progress. It’s loosely based on the decline of Dr. Walter Freeman who was a fascinating historical figure who invented and popularized the [transorbital] lobotomy in the ‘40s and sort of fell from grace in the early ‘50s with the advent of more stealthy ways to subdue the anxieties and peculiarities of the population.

Mental illness is pervasive through all my movies to some degree, but I was particularly interested in the idea of the procedure as a cure all. And, for me, the obvious and frightening similarities to entertainment and the procedure that we go and subject ourselves to in sometimes daily fashion, of entertainment.

HEN: I like how the menace of Jeff Goldblum’s character slowly evolves through the film, how different a movie is this without him?

RA: The way casting works for me is you rebuild and reconfigure and re-emphasis the film in relationship to the context of the performer, or the attributes of a performer.

The movie is just as much as anything about dependancies and parasitic relationships. For me, I think just as much about the parasitic relationships between the industry and the form and the audience as much as that between Fiennes and Andy. Those are meant to be parallels between one and the other whether people are consciously aware of it, it’s what I’m thinking about when I’m making the thing.

Fiennes is very much using Andy as a witness to promote the one-dimensional narrative of the benefit of the procedure. As much as anything, the film is a critique of narrative as a potentially outmoded envelope for meaning and the delivery of information. I’m really curious if it is even wholly functional anymore as something that is beneficial, as the only beneficial way it can function is as an intoxicate. It intoxicates into nostalgia. It intoxicates us into validation of our world views. Is it even possible anymore to unbridle us from our definitive conclusions about the world? The movie very much looks at that in both its subject and it’s form, hopefully.

HEN: Without giving too much away here, Tye Sheridan’s character is sort of lost at the beginning, but is he free at the end?

RA: In the history of the American archetype, being lost is being free … Lunging into the unknown. Unmooring one’s self and becoming lost is only equatable with freedom. I think that’s the only honest way to look at it.

The paradox is us wanting freedom but wanting governance. That’s the Trumpian paradox of purportedly selling freedom while actually instituting fascism, which isn’t his alone, we have a long history of that. And it’s the same thing Fiennes is doing in the film.

HEN: Characters in your films are often on a journey — literally or figuratively — where the final destination isn’t pretty. It’s not what they or the audience expect it to be. It’s not really a payoff. Why about that drives your interest?

RA: I’ve always sort of been turned off by the bill of goods that Hollywood has been selling us that there is arrival. Whether it’s in episodic television in sitcoms or dramatic consumer films, the idea is we arrive somewhere, we arrive at a conclusion. This is also one of my problems with the usefulness of narrative. If we are taught over and over again by our stories that we arrive, but we find in life that we never arrive and if we do arrive, our expectations aren’t met. How are we actually dealing with the material of the world? We’re not.

I’m interested in limitations. I think the film is praise for an epiphany of the limited universe. I think at the end of the film that’s what is confronted and hopefully that’s what confronts the audience.