More than 200 years after his birth, Edgar Allan Poe’s stories remain as compelling as they are horrifying. And, if he were still alive to cash the residual checks, he’d know they’re also highly adaptable. His stories have been turned into plays, movies, radio and TV shows, and even comic books.

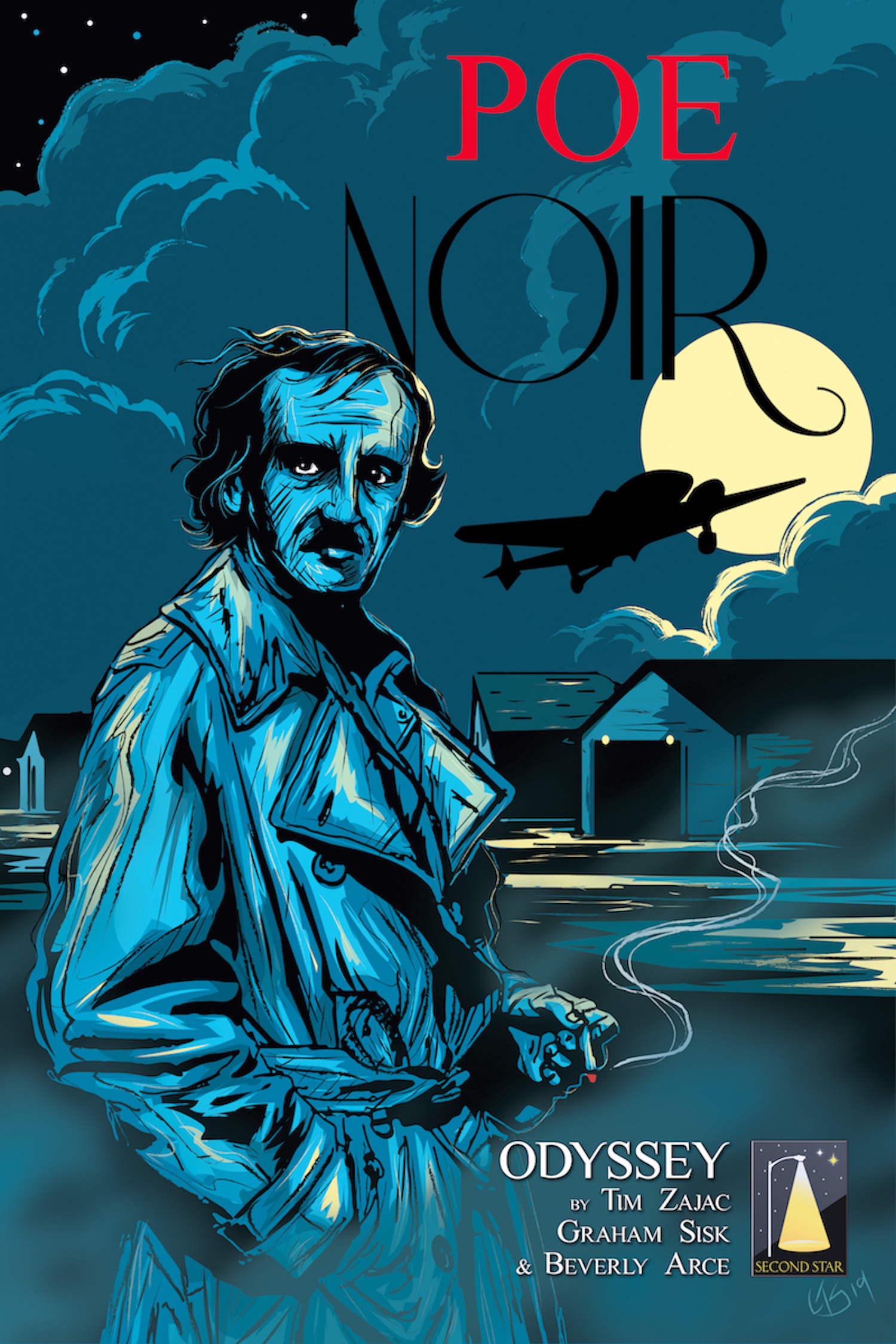

The newest comic adaptation, Poe Noir, brings Poe into the realm of Raymond Chandler novels or 1940s-1950s film noir.

Created by writer Tim Zajac, it’s a clever twist that works surprisingly well, with something to enjoy for fans of both genres. Each issue is a quick ride through one of the author’s numerous works, with illustrations in glorious black and white by artists Graham Sisk or Beverly Arce. The latest issue is an adaptation of The Raven, celebrating its 175th anniversary in January.

Halloween Every Night talked with Zajac about his love of Poe, movies, the creative process, and life as an indie comic maker.

Halloween Every Night: Tell me about your love of Edgar Allan Poe. How did this “romance” begin?

Tim Zajac: It was a dark night, in a club, back in ’68… Seriously, though, like most people in the U.S., I discovered Poe in school. It started with The Raven and The Tell-Tale Heart, but then in high school I read The Cask of Amontillado, and that’s where I was hooked. There’s something about the psychology in his writing, how he can make even the most crazy sound reasonable and brilliant. That was always striking to me.

HEN: What about film noir and detective novels, because that’s the other part of this. Where did that start and what are some of your favorites?

TZ: Film noir was also a phenomenon I discovered in school, this time in college film classes. The appeal was two-fold — I was first blown away by the visual style, which relies on high-contrast lighting, and the interplay of light, shadow, deep focus, and skewed composition. I also fell in love with how that was married to a distinct thematic and psychological style—the dark underbelly of society and the individual. The visual mirrored the thematic, in essence.

What made it even more appealing was how flexible it was, in that it transcended genre. Sure, film noir is best known as the playground of the hard-boiled detective, but it goes way beyond that—there are film noir westerns, like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, film-noir sci-fi, like Blade Runner, and more.

HEN: It’s not an obvious choice to merge these two things together, so when did the idea strike you?

TZ: It may not be obvious on the surface, but sitting in that film class years ago, learning about the DNA of film noir pointed me right back to Edgar Allan Poe. Here’s the lineage, going backwards in time — many films of the classic noir period of the 1940s and 1950s took inspiration from the pulp novel movement that began decades before. In those stories, they were doing the same thing, exploring the shades of grey in the world, the not-so-nice things that were often just below the surface. That literary tradition goes all the way to Poe. He was the first prominent guy in American writing to go dark, so to speak. So in that sense, we have a through-line from Poe to noir. And when I figured that out, my head immediately went to thinking about how Poe could be adapted in that way.

HEN: Indie comics often have the problem of being able to get the right writer and right artist coming together for the right work. Words and pictures work together very well here. Tell me about that process.

TZ: It takes some patience, to be sure. I met artist Graham Sisk through Craigslist, believe it or not.

The initial ad gave me dozens of responses that were not so good, but after 60 or so, there was Graham. Some of his samples were along the lines of what I knew Poe Noir needed to look like, so I had to reach out. A few emails and phone conversations proved that we clicked creatively, and now he is a valued collaborator. I think it required both parties to be open to getting to know one another a little—once we figured out some common ground, we could run with it.

With Beverly Arce, who began contributing with the Poe Noir: Odyssey issue, our partnership came as a result of seeing one another at comic conventions for well over a year. She taught me the concept of the “booth buddy,” which is a fun way of describing the mini-community that tends to rise out of doing show after show. I really liked her art styles and variations, and I even had her do a few commissions at these shows to see how she could approach material I was working on. After that, and getting to know her over time, I knew she’d be a good fit and a joy to work with. So in both situations, effort was put into connecting with these artists and collaborators, and it really paid off.

HEN: Each book is a breezy and slightly surreal ride through a Poe story, what are the decisions like to include this story element and exclude that one?

TZ: It really varies between each Poe story I am adapting. With our adaptation of A Descent Into The Maelstrom, for example, I knew that regardless of whether or not it was a whirlpool, I needed to include something that had pull to it, something that drew you in. That led to the idea of the singularity in the box, hence the title of The Gravity of the Situation. And then I kept things on a boat, which served both the original Poe tale and the comic story itself. The Raven, on the other hand, is a poem about love and loss, and it’s probably one of the most beloved American poems of all time. I knew that I had to keep it abstract, and wanted to avoid direct comparisons to Poe’s timeless words, which I could never match, of course. That’s why the majority of that story is without dialogue or narration. Nonetheless, there is plenty of love, loss, and longing to it—and hopefully a little catharsis, too, which might take it beyond the original poem.

HEN: Your latest book is the spin on The Raven. Is the process easier now than it was when you started?

TZ: Yes and no—it again falls upon which material I am adapting. I found our Maelstrom adaptation much easier than The Raven, in that it had those more direct analogues, like the whirlpool becoming the singularity. Those clicked quickly for me. With The Raven, I was stuck for years on the Raven not being a bird, but a plane. Figuring out how to make story sense of that was agonizing, and it really took patience on my part. I really had to let the idea sit with me over a long period of time. Sometimes that’s just how it goes.

HEN: What’s the path ahead for Poe Noir?

TZ: There will be at least a bit more of us adapting his broader catalogue, before we move to a second phase—the DuPin stories. Poe perhaps singlehandedly invented the detective story, and was an early adopter of serial storytelling with his DuPin detective character, who appears in three of his stories. We’re going to start exploring that world next.