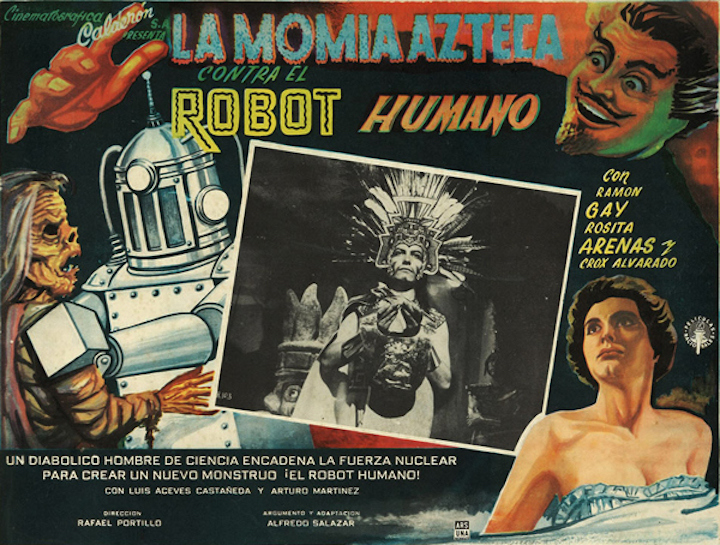

Roundly ridiculed but strangely historical, the third film in a goofy franchise of Aztec mummy movies arrived on Mexican movie screens in the summer of 1958. No one knew at the time it would become the first ambassador of Mexican horror to American audiences. In fact, it’s still pretty hard to believe it now.

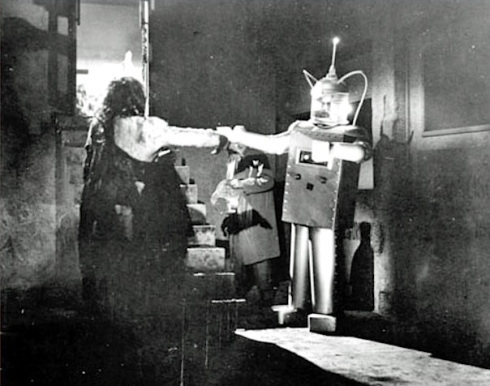

The Robot vs. The Aztec Mummy combined bad makeup and special effects, over the top acting, and recycled parts of previous movies into a soup of B-movie badness that has lived a long and checkered existence on American TV screens since the 1960s. But it wasn’t until Guillermo del Toro came along that Americans knew much else about Mexican horror.

Doyle Greene, author of the books Mexploitation Cinema and The Mexican Cinema of Darkness, spoke to Halloween Every Night about the lasting value a bad movie can have.

Halloween Every Night: Despite it’s wonderful badness, what would be one or two things you’d want people to look for, or think about when seeing The Robot vs. The Aztec Mummy?

Doyle Greene: Well, whether it has any value as timeless art could be debated, I guess. The main point being that while the film may not be great art — whatever that even means — it does have historical and social relevance. I think it merits being taken seriously at that level. As far as subtext, the filmmakers are offering a representation of concerns and issues that Mexico was tackling at the time, like modernization.

It’s not just what might be going on culturally, economically, politically, or socially, but the pressures applied by supply and demand or industry production and audience consumption. But, in the end, they’re great fun however anyone wants to look at them and there’s a lot to be said for that! As the saying goes, “They just don’t make ‘em like they used to.”

HEN: What can you tell me about the making of the movie?

Despite the very low-budget look, these films were done by established studios with established industry producers and directors and well-known stars in Mexico. In the US, low-budget horror tends to be synonymous with independent producers and directors and name actors in the twilight of their careers. That wasn’t really the case with Mexican horror films.

Also, the Mexican film industry was heavily controlled by the Mexican government. Churubusco-Azteca, the studio that made the Aztec Mummy series among many others, had the majority of its stock bought by the government in 1957 and completely nationalized in 1960. There was a certain amount of economic support but, simply put, the films were expected to turn a profit and often self-censored their content rather than having official censor boards do it for them. The oft-voiced criticism was the Mexican film industry devolved into churning out assembly-line genre movie like action-adventure, horror, and romantic-comedies, and it was not uncommon for films to freely juxtapose several genres in the same film from scene to scene and not do it ironically. Melodrama also tends to have a very pejorative connotation in American and European culture, but in Mexico it doesn’t.

The Mexican film industry at the time was fairly exclusive. Rene Cardona directed the Wrestling Women films and also co-starred in The Brainiac. Abel Salazar produced The Brainiac as numerous other Mexican horror films and also starred in The Brainiac. His brother Alfredo Salazar was a prolific screenwriter who wrote or co-wrote the Aztec Mummy trilogy and the early Wrestling Women films. Guillermo Calderon Stell produced the Aztec Mummy trilogy as well as the Wrestling Women films. Rafael Portillo directed the Aztec Mummy trilogy but as an industry veteran, did films across genres and relatively few in horror.

HEN: The first half of the film recaps the two previous Aztec Mummy films — in which a woman is sort of the pawn between two scientists. One experimenting on past life regression and the other eager to rip off some ancient jewels. Was the long recap sort of a consideration to audiences who might have been coming late to the whole Aztec Mummy thing or just laziness?

DG: To be sure, it looks like flat-out padding and that back story can be interminable.

I think there’s only around 30 minutes of new footage and an hour-long film is a pretty slight running time to begin with. The trilogy of Aztec Mummy, Curse of the Aztec Mummy, and The Robot vs. the Aztec Mummy were all filmed at the same time – a very common tactic now with Hollywood franchise films – and the first two were released in 1957 and the third in 1958.

But I agree the recap in the first half is a way to provide the back story for unfamiliar viewers. If a typical viewer goes to one of the many films in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, there’s not a lot of effort needed to provide an extended back-story. By that point viewers know – or are expected to know – what Tony Stark is all about. There’s no need to have an extended flashback from the first Iron Man to explain.

HEN: The filmmakers also got some glaring things wrong about their own history, did it matter at the time?

DG: You know, I have to be honest and it wasn’t until recently I became more aware of the level of historical inaccuracy, up to and including how it freely conflates Aztec and Mayan culture. That’s pretty stunning considering the films fall under the umbrella of Mexican national cinema.

I’m not defending that, but I think it does tie into the ideological message. From the late 1950s to the late 1970s, the pervasive struggle was between the past and the present to determine the future. The past of pre-modern Mexico, like Aztecs and Mayans, and the history of European colonialism are often represented by villains who are paranormal and often resurrected forces like vampires, mummies, warlocks and witches. It becomes imperative to not just stem the threat, but eradicate it entirely from ever returning to plague Mexican society again.

There’s the occasional mad scientist too. As you pointed out, Robot/Aztec Mummy is a good vs. bad scientist battle. The evil scientist is Dr. Krupp – and I don’t think it’s a coincidental choice of name, as Krupp references a massive German military-industrial corporation that was tied to the Third Reich. Krupp’s evil stems not so much from technology — his Robot — but his determined efforts to pry into Mexico’s past, with his plundering Aztec treasure an act of European colonial conquest.

Krupp unleashes things that are, rather literally, better left buried and forgotten. The catch is that good scientist Dr. Almada is pursuing his own study of Aztec civilization for more altruistic reasons and more esoteric means, but ultimately the message is that Almada also may have been wise to leave Mexico’s past alone and just let it rest in peace.

HEN: Please explain to me why a wrestler was added to a movie where you already have an evil scientist, a robot and a mummy?

DG: That’s a key issue.

In Mexican horror films, science is generally treated favorably and it’s not uncommon to have a good scientist as a key character actively working to vanquish the threats from the past. The heroes often represent modernity and modern Mexico undergoing numerous changes in the 20th century and guiding Mexico on a course of modern progress.

In the Aztec Mummy films the wrestler is more of an assistant to the scientist – which is to say the scientist is the brains and the wrestler is the brawn and could also supply some gratuitous lucha libre-style action when the going gets slow.

Pro wrestling is a simple, melodramatic “good vs. evil” struggle and is a cultural-national institution in Mexico dating back to the 1930s at least. Having Dwayne Johnson do a film titled The Rock vs. the Zombies where he plays his ring persona alternating between zombie hunting and stopping at WrestleMania or Summer Slam to have a straight wrestling match would sound completely absurd here, but this was the standard formula for the films starring El Santo or Blue Demon or any famous Mexican luchador in the 1960s. Since the films were successful commercially, the studios keep making more as long as there was a demand.

HEN: How did Mexican horror movies change from there?

DG: The late 1950s through the late 1970s was the heyday of these kinds of films and the 1960s was arguably the apex. But by the late 1960s, it was already running its course.

Like the rest of the world, Mexico went through a great deal of social upheaval. One defining moment was the Tlatelolco Massacre on October 2, 1968 in which hundreds of demonstrators were gunned down by police and military forces. After that, the idea of Santo saving the day protecting women and children from Martians seemed kind of corny.

There’s only so many variations on the masked wrestler vs. monster theme before it becomes diminishing returns. Santo was doing espionage films and even a Western by the end of his career. Those are pretty bizarre films. Ultimately, as the popularity declined and the market began to dwindle, the industry responded with alternate products.

Also, the international market and particularly competition from ‘Eurotrash’ horror films offered more sex and violence than was permitted within the constraints of the lucha libre genre. Mexican horror moved into more explicit, and I’d also say more avant-garde area.

Juan Lopez Moctezuma’s Alucarda in 1975 would be an example and it seems like a cross between Pier Paolo Pasolini and Jess Franco. It shows little influence from the Mexican horror film tradition in fact, Alucarda was even shot in English for better overseas marketing prospects. Rene Cardona Jr. would be another director who gained fame –or infamy – for his exploitation films in the latter 1970s and beyond.